COLIN SIMPSON

How the Space Age Ended Up as a Museum Exhibit

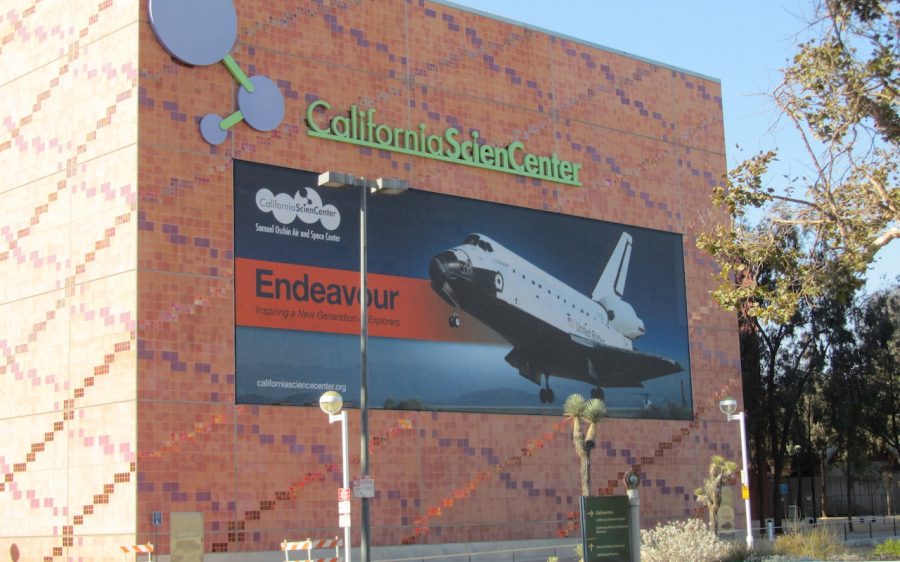

Space shuttle Endeavour, California Science Center, Los Angeles

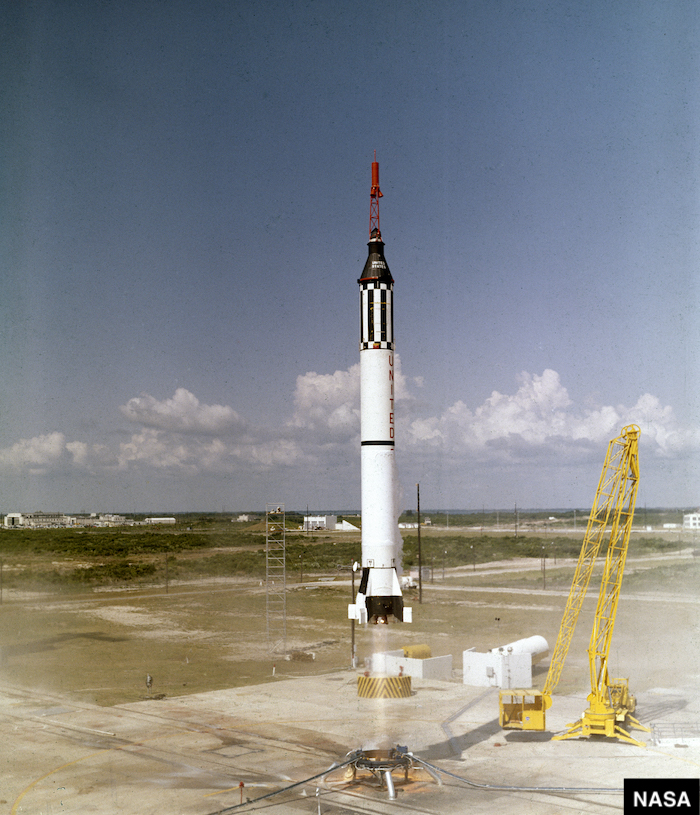

I WAS about to step aboard one of Captain Nemo’s submarines at Walt Disney World in Florida, when suddenly everyone around me started shouting and pointing.

Gazing up, I saw what they were looking at – the second space shuttle mission was blasting off from the John F. Kennedy Space Center 60 miles away.

The shuttle Columbia was a small white speck rising steadily on a column of smoke. For someone who had been entranced by space travel since childhood, this was quite a moment.

The shuttle Columbia was a small white speck rising steadily on a column of smoke. For someone who had been entranced by space travel since childhood, this was quite a moment.

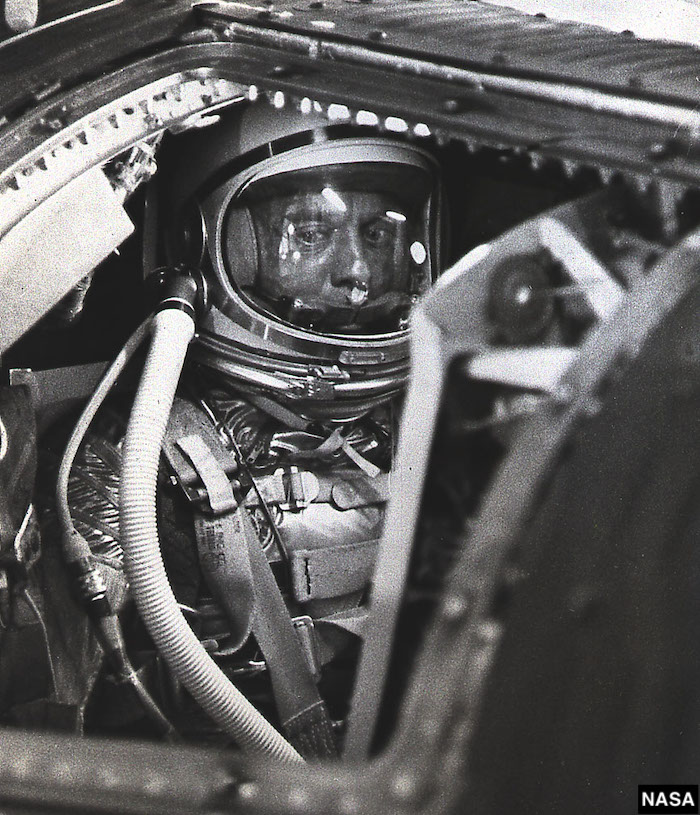

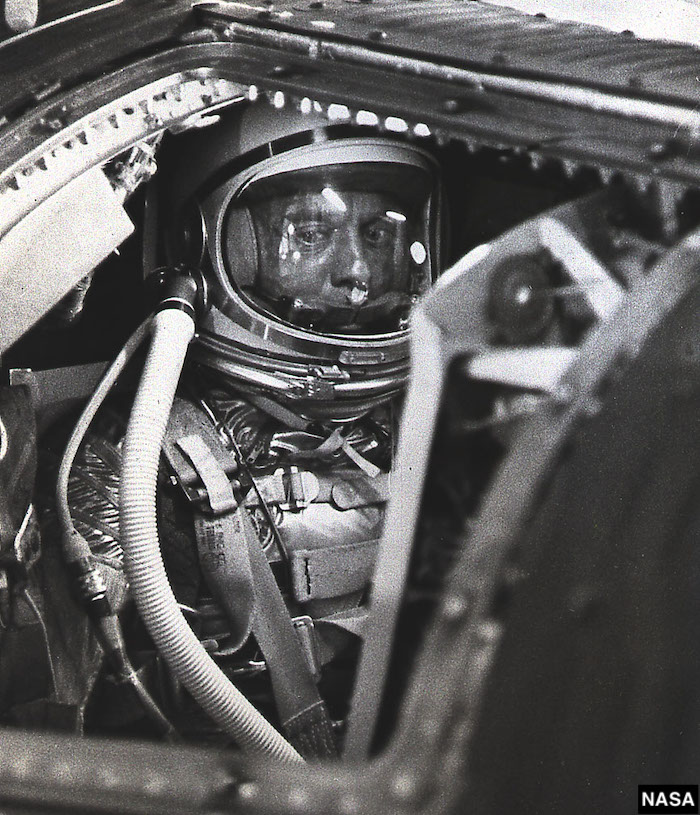

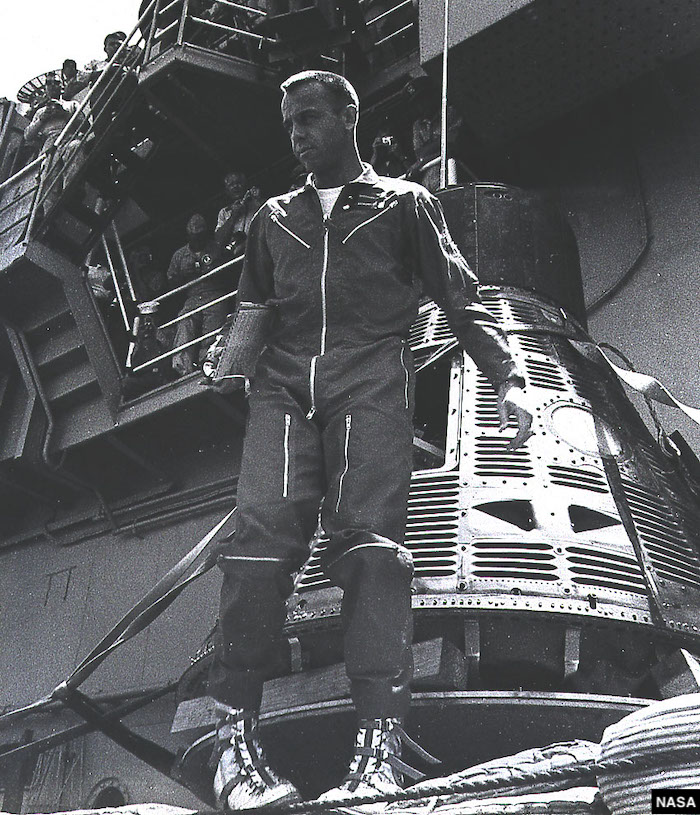

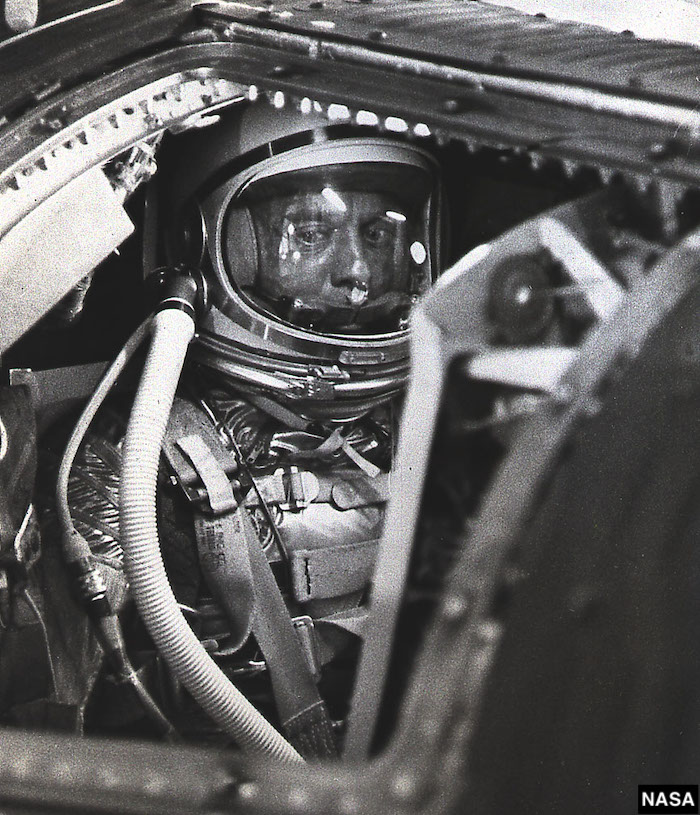

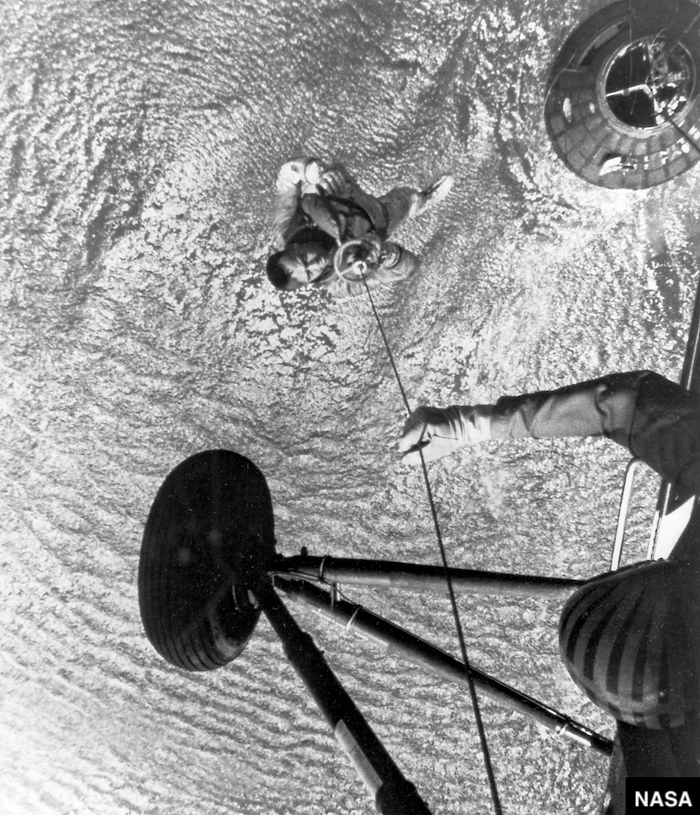

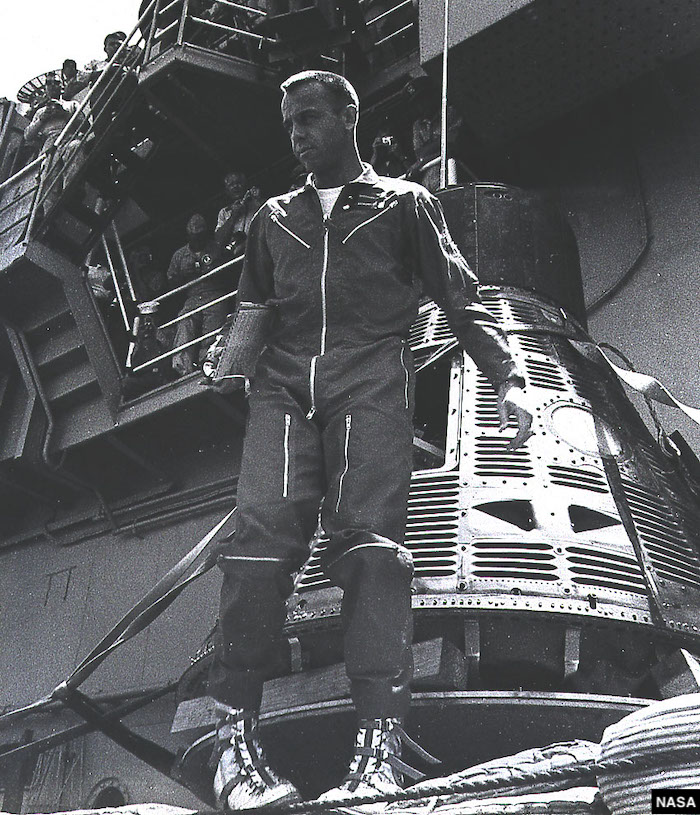

When I was at school Freedom 7, the Mercury capsule Alan Shepard flew in when he became America’s first astronaut in 1961, was displayed at a museum in my hometown. If this was intended to create an interest in space among young people, then it certainly worked with me.

I visited the museum in Edinburgh often to peer at the spacecraft, which was clad in protective clear plastic. I listened as John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, gave a speech there.

And I never missed an episode of a BBC TV science show called Tomorrow’s World which covered the run-up to the first Moon landing in lavish detail.

That shuttle launch happened in November 1981, and I saw it as I was nearing the end of an East Coast tour from New York to Florida. I also visited the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington to see the space exhibits and touch the little piece of moon rock on display.

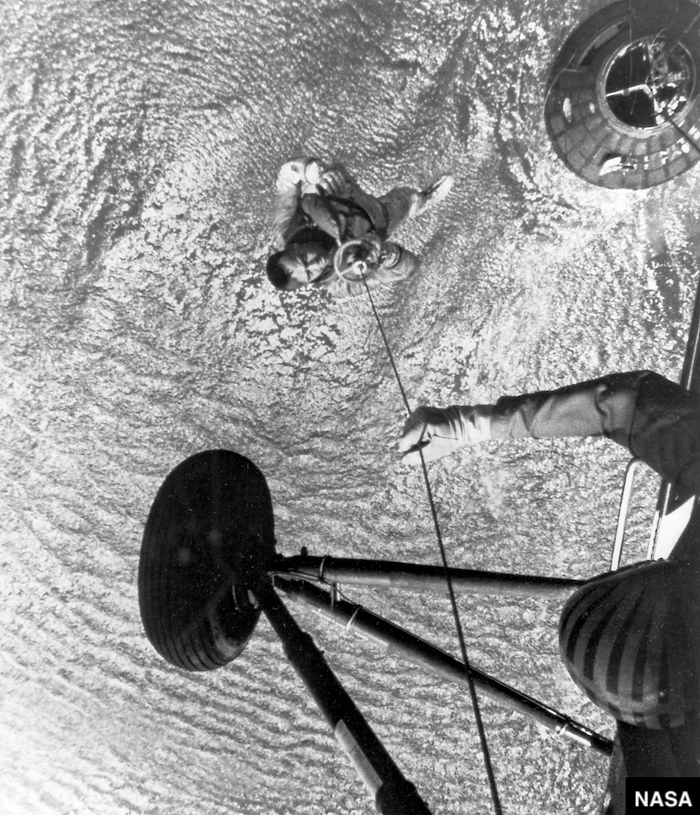

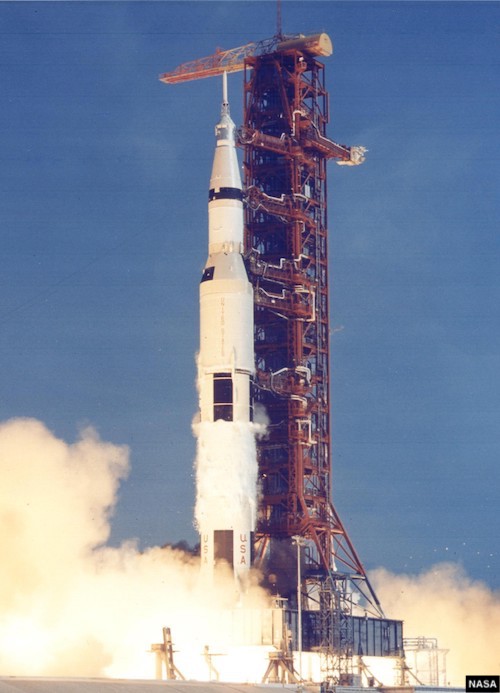

A few days after witnessing the launch from afar I went to the space centre. I travelled on a bus along the road on which the shuttle had been transported to Launchpad 39A where the takeoff had happened.

The same roadway had carried the giant Apollo 11 Saturn V Moon rocket to the pad. While at the complex, I gawped in wonder at the sheer size of a Saturn V that lay in sections along the side of a road.

The Dish, a film about a communications team in Australia that helped to relay TV pictures of the Apollo 11 moon landing, was released in 2000. A colleague in his twenties who liked the movie said he wished he’d been alive during that pioneering era of space travel to witness it all first-hand. I was surprised by this remark, as if he had been he would no longer be young with most of his life ahead of him. But I guess it was a reflection of the fascination space travel holds for so many.

Certainly, my interest in the subject continues to this day, and on a more recent visit to the States I was delighted to get to see a space shuttle, Endeavour, at much closer range.

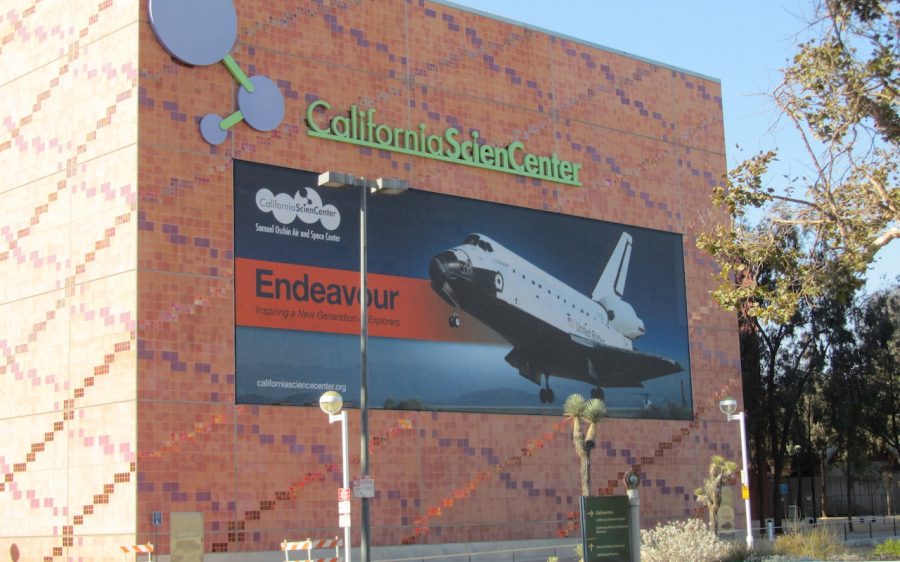

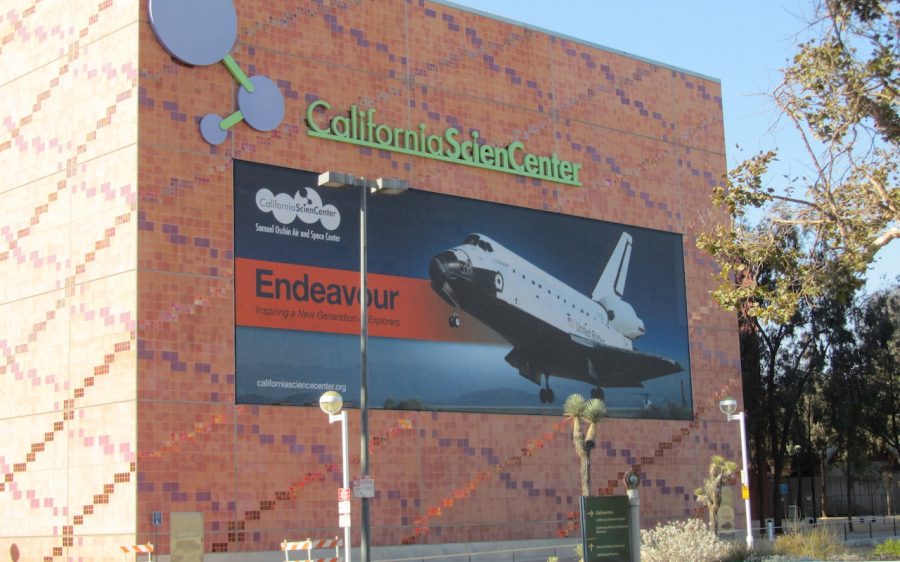

It’s on permanent display at the California Space Center in Los Angeles. It’s obvious as soon as you arrive that this is no ordinary museum.

Standing next to the car park is a unique trainer version of the A-12 Blackbird, a supersonic high-altitude spy plane developed and built by Lockheed for the CIA as a successor to the U-2. The A-12 was produced as a “black op”, flew for only a few years in the 1960s and its existence remained secret until the mid-1990s.

The museum has other historic aviation exhibits and there are sections devoted to ecosystems, innovation and the life sciences. But for me the standout attractions were the spacecraft from each stage of the US’s spaceflight programme.

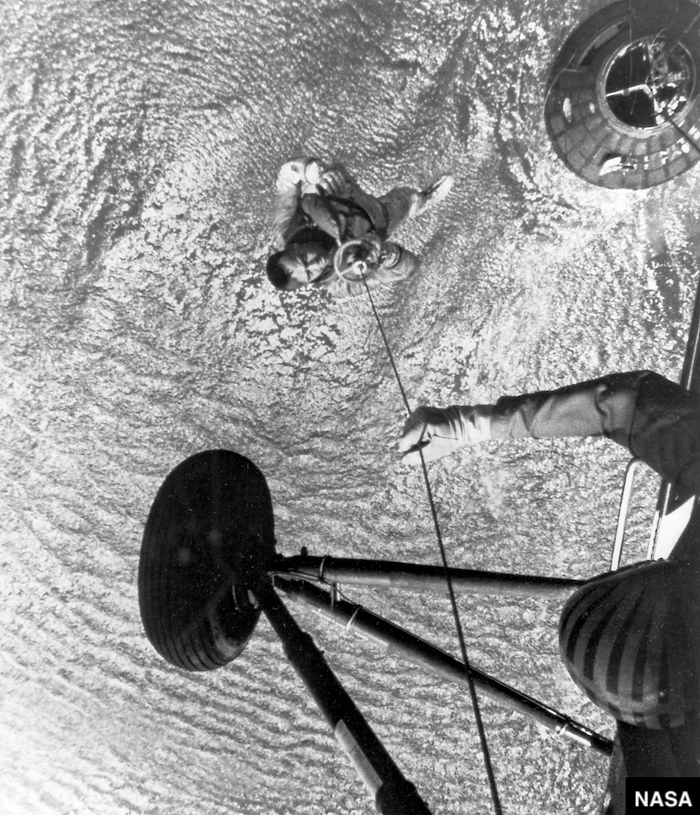

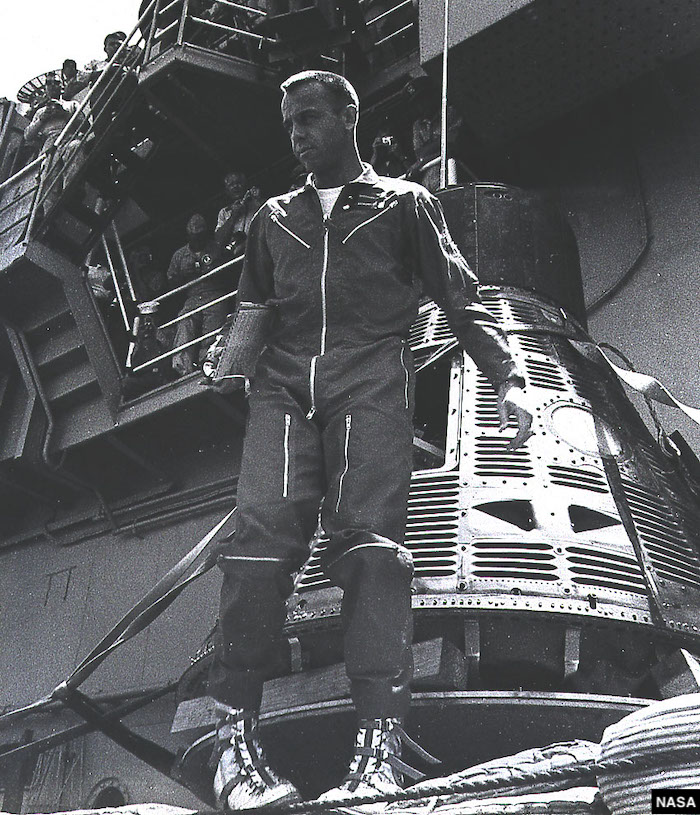

There’s the Mercury capsule that carried a chimpanzee called Ham into space in preparation for Shepard’s flight. There’s the two-man Gemini 11 capsule used by astronauts Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad in 1966.

And there’s the three-man Apollo command module that linked up with an orbiting Russian Soyuz spacecraft in 1975 in the first international human space flight mission. This module had been built to fly to the Moon in a planned Apollo 18 mission that was cancelled after funding for the programme was cut.

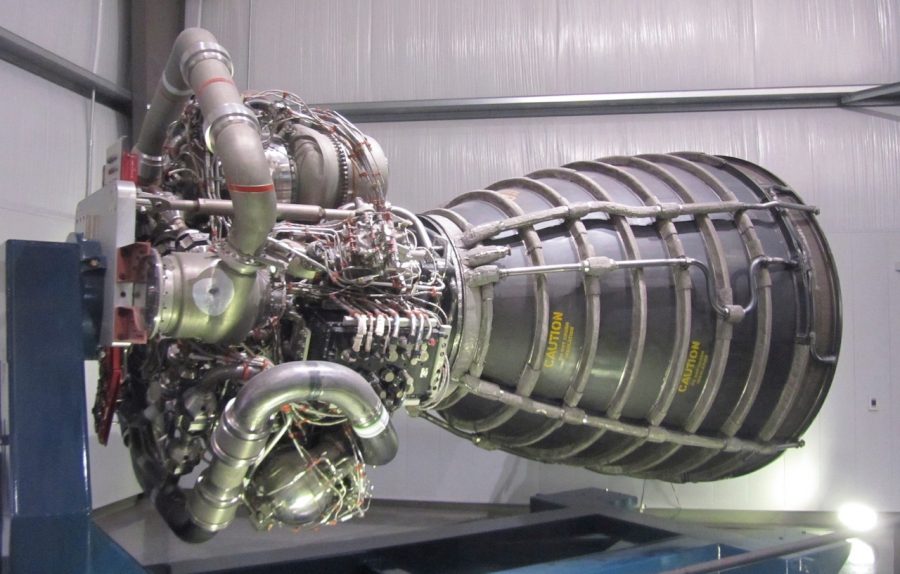

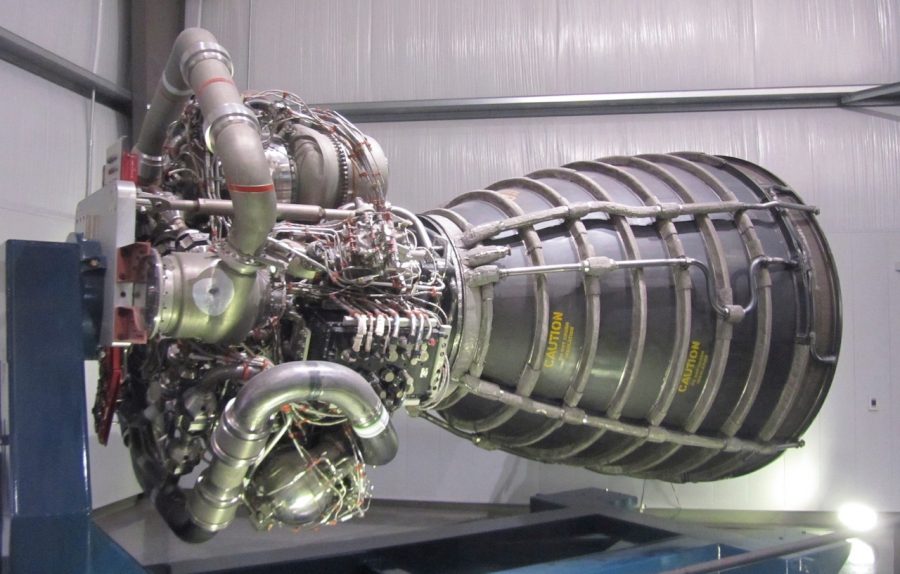

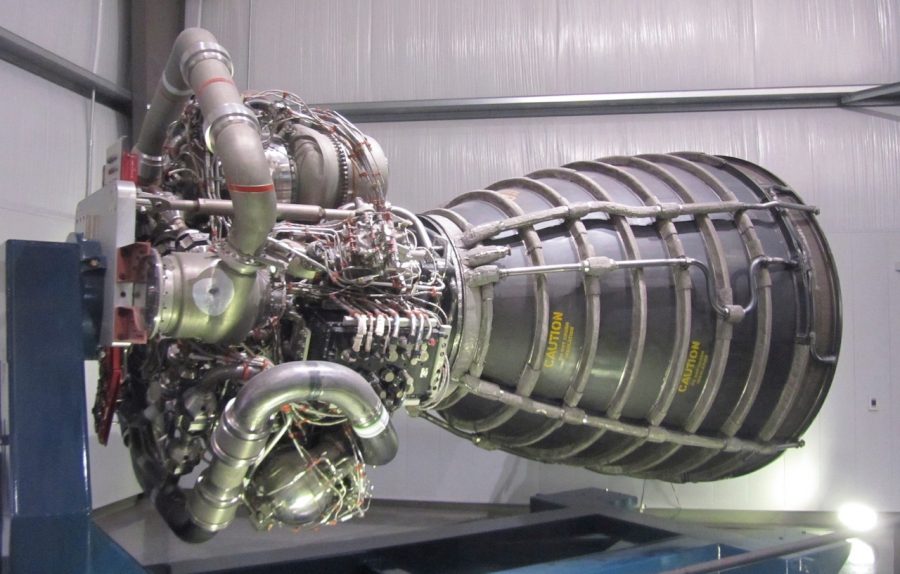

And then there is Endeavour. Those early capsules were small – it was said that you didn’t get into Mercury, you put it on. But the shuttle is, by comparison, enormous, and you can’t help being impressed when you see it up close. I spent ages wandering around it, examining the scorch marks on the heat-resistant tiles and the engines, and marvelling at the sheer bulk of the spacecraft.

I thought about the astronauts who had flown on her 25 missions, the courage needed to embark on such journeys – particularly in view of the shuttle disasters – and the sights they would have seen through her windows.

There are fabulous videos of Endeavour being eased through the streets of LA on her way to the museum, the wings barely squeezing past trees and lampposts (see below).

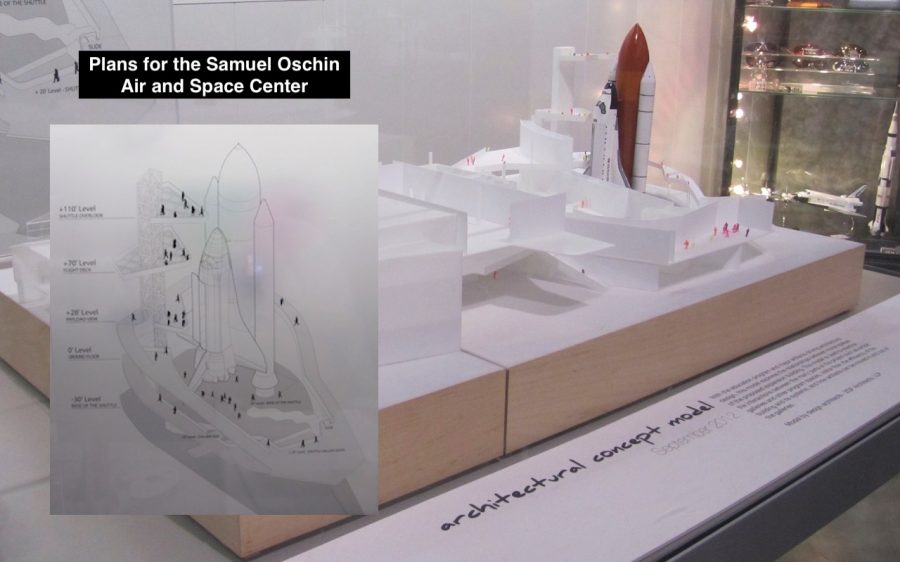

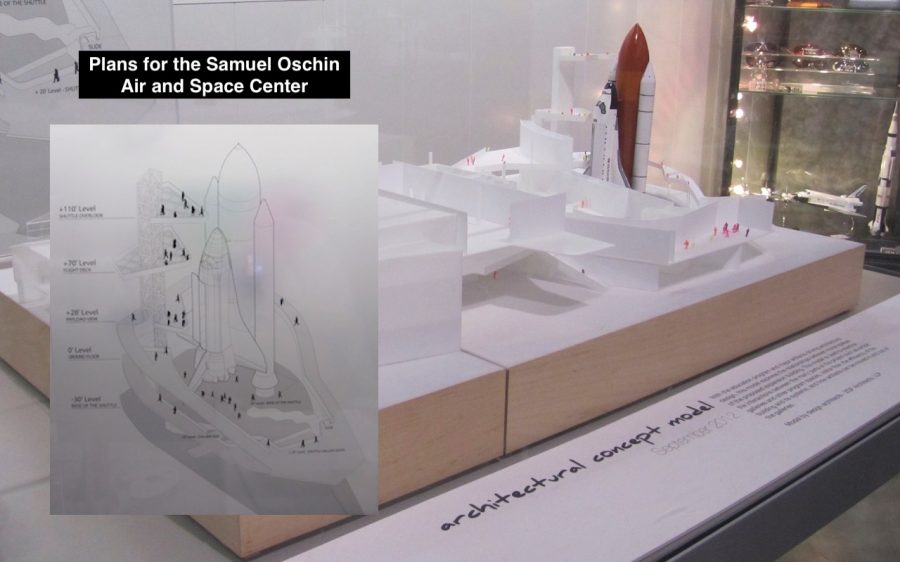

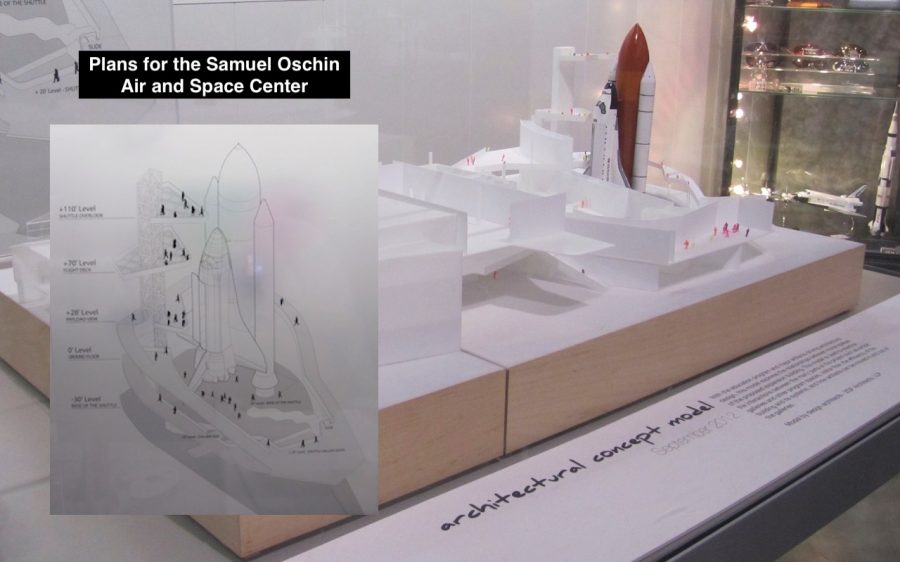

The shuttle is displayed horizontally in a hangar-like pavilion, but there are plans to show her standing vertically in a new building, the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center. She would be attached to the other shuttle components, an external fuel tank and two solid-rocket boosters. This would provide a unique chance to see an entire 60 metres high shuttle vehicle in launch position.

I checked with the museum to see how the plan was progressing, and was told that it’s hoped construction will begin soon. It will then take three years to complete the project.

In the Sixties, as the US closed in on the Moon with successive flights and then triumphantly reached its surface, human space exploration felt like the future.

But today, as we look back 50 years to that first Moon landing and spacecraft have become museum exhibits, it seems to belong to the past. Tomorrow’s World has become yesterday’s world.

Mankind lost the capacity to send astronauts to the Moon after the final Apollo mission in 1972 following mission cutbacks. It seemed a strange decision at the time, and even more so looking back now. All the expense, the effort, the expertise, the resources devoted to putting people on the Moon; the lives of three astronauts killed when Apollo 1 caught fire.

Then, a little more than three years after the first landing, the Apollo programme was wound up, the ability to reach another celestial body surrendered. The US has not been able to launch people into space since the last shuttle flight in 2011.

The mission completed by the California Science Center’s Apollo capsule involved climbing 230 kilometres to low-Earth orbit, rather than flying 384,000 km to the Moon, so it did not need the mighty Saturn V to propel it. Instead, it was launched on a far smaller and skinnier Saturn IB, and in order to fit the launchpad the vehicle had to be propped up on a stand. This seems as good a metaphor as any for the reduced horizons and ambition of America’s space programme.

Decades of chatter about human missions to Mars have come to nothing. Is there any reason to think all the current talk about returning to the Moon and going on to Mars will bear fruit?

NASA’s Artemis programme is intended to land a man and the first woman on the Moon in 2024. However, space expert Miriam Kramer, writing for Axios on July 2, said the giant rocket the programme will use, the Space Launch System, is “years behind schedule”. She added that it was not clear whether Congress would allocate the money needed to return to the Moon by 2024.

And she quoted John Logsdon of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute as saying: “The program we have executed to return to exploration is in no way comparable to Apollo in intensity or commitment.”

The growth of the commercial launch sector, the prospect of suborbital tourist joyrides and the rest are all very well. But they hardly compare to the exploits of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, and the other Apollo crews.

It’s strange to think that I, and others my age, have in our lifetime witnessed the transformation of science fiction into reality, and then into history.

Top tip: Endeavour is a popular attraction so timed reservations are needed every day – check out the museum’s website (link below) for details.

Updated January 2020

Return to Tranquility Base

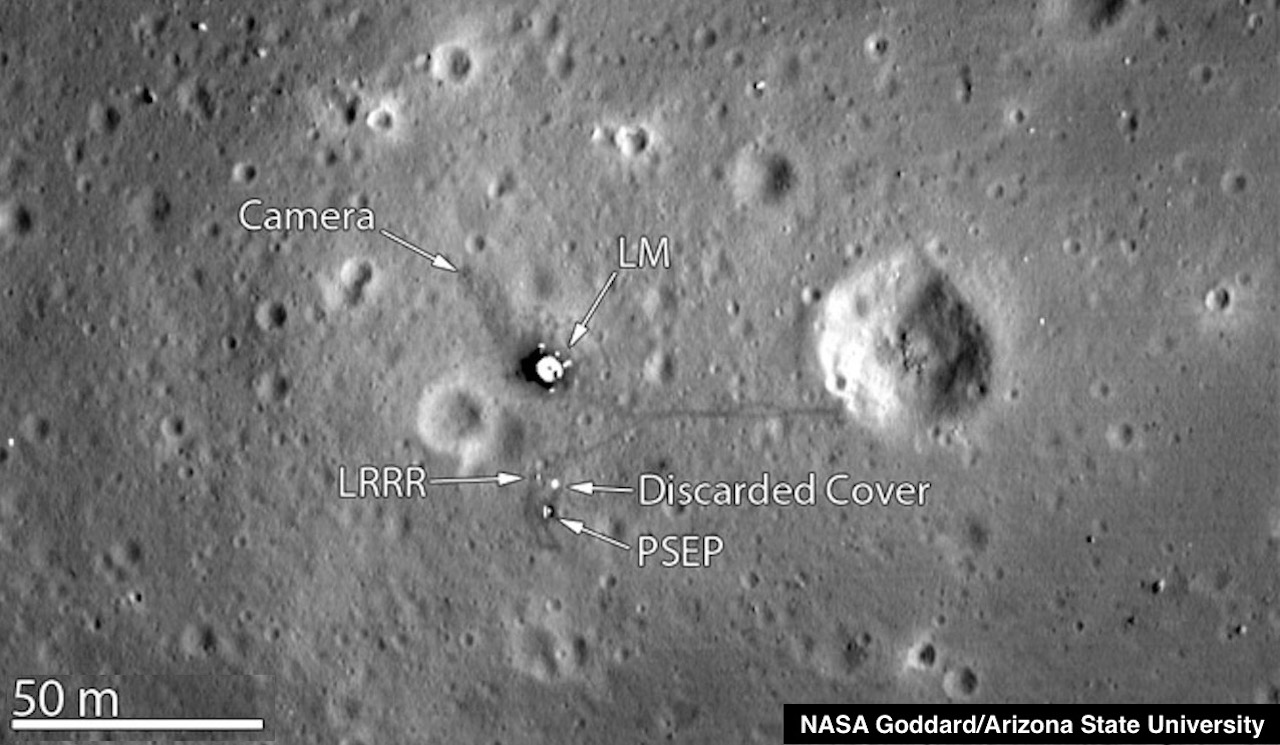

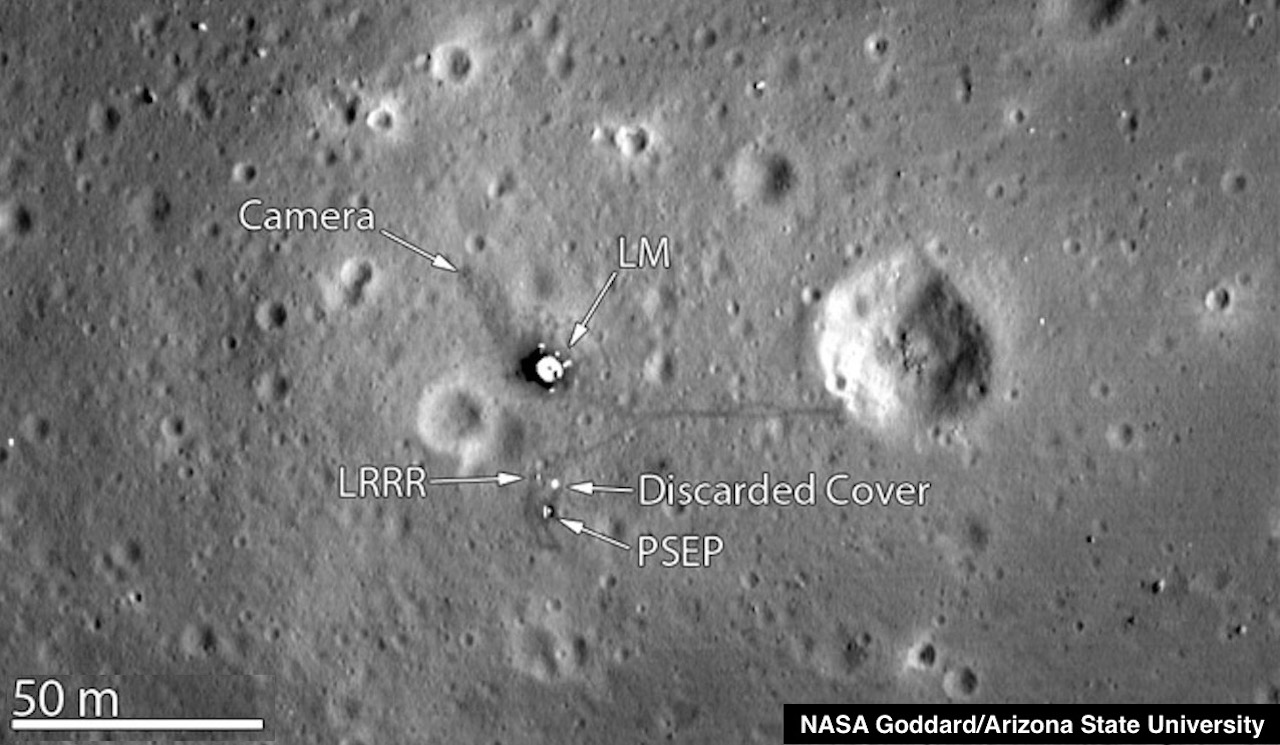

THIS remarkable photo shows the Apollo 11 landing site, known as Tranquility Base, viewed in 2009 from NASA’s unmanned Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The object tagged LM is the descent stage of the Eagle lunar module, left behind when the crew blasted back into space in the ascent stage. The dark tracks were made by the footsteps of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

They lead to a TV camera and two scientific instruments indicated by the initials LRRR and PSEP that were placed on the surface by the astronauts. The discarded cover was from one of the instruments. The LRRR – Laser Ranging Retroflector – was designed to provide information about the distance between the Moon and the Earth, and according to NASA it’s still providing data to this day.

The track to the right of the LM was formed when, towards the end of the Moon walk, Armstrong decided to have a look at a crater called Little West. While there, he took the second photo looking back at the lunar module, with his shadow in the foreground.

MORE INFO

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

LET'S KEEP IN TOUCH!

Endeavour

Encounter

COLIN SIMPSON

How the Space Age Ended Up as a Museum Exhibit

Space shuttle Endeavour, California Science Center, Los Angeles

I WAS about to step aboard one of Captain Nemo’s submarines at Walt Disney World in Florida, when suddenly everyone around me started shouting and pointing.

Gazing up, I saw what they were looking at – the second space shuttle mission was blasting off from the John F. Kennedy Space Center 60 miles away.

The shuttle Columbia was a small white speck rising steadily on a column of smoke. For someone who had been entranced by space travel since childhood, this was quite a moment.

When I was at school Freedom 7, the Mercury capsule Alan Shepard flew in when he became America’s first astronaut in 1961, was displayed at a museum in my hometown. If this was intended to create an interest in space among young people, then it certainly worked with me.

I visited the museum in Edinburgh often to peer at the spacecraft, which was clad in protective clear plastic. I listened as John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, gave a speech there.

And I never missed an episode of a BBC TV science show called Tomorrow’s World which covered the run-up to the first Moon landing in lavish detail.

That shuttle launch happened in November 1981, and I saw it as I was nearing the end of an East Coast tour from New York to Florida. I also visited the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington to see the space exhibits and touch the little piece of moon rock on display.

A few days after witnessing the launch from afar I went to the space centre. I travelled on a bus along the road on which the shuttle had been transported to Launchpad 39A where the takeoff had happened.

The same roadway had carried the giant Apollo 11 Saturn V Moon rocket to the pad. While at the complex, I gawped in wonder at the sheer size of a Saturn V that lay in sections along the side of a road.

The Dish, a film about a communications team in Australia that helped to relay TV pictures of the Apollo 11 moon landing, was released in 2000. A colleague in his twenties who liked the movie said he wished he’d been alive during that pioneering era of space travel to witness it all first-hand. I was surprised by this remark, as if he had been he would no longer be young with most of his life ahead of him. But I guess it was a reflection of the fascination space travel holds for so many.

Certainly, my interest in the subject continues to this day, and on a more recent visit to the States I was delighted to get to see a space shuttle, Endeavour, at much closer range.

It’s on permanent display at the California Space Center in Los Angeles. It’s obvious as soon as you arrive that this is no ordinary museum.

Standing next to the car park is a unique trainer version of the A-12 Blackbird, a supersonic high-altitude spy plane developed and built by Lockheed for the CIA as a successor to the U-2. The A-12 was produced as a “black op”, flew for only a few years in the 1960s and its existence remained secret until the mid-1990s.

The museum has other historic aviation exhibits and there are sections devoted to ecosystems, innovation and the life sciences. But for me the standout attractions were the spacecraft from each stage of the US’s spaceflight programme.

There’s the Mercury capsule that carried a chimpanzee called Ham into space in preparation for Shepard’s flight. There’s the two-man Gemini 11 capsule used by astronauts Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad in 1966.

And there’s the three-man Apollo command module that linked up with an orbiting Russian Soyuz spacecraft in 1975 in the first international human space flight mission. This module had been built to fly to the Moon in a planned Apollo 18 mission that was cancelled after funding for the programme was cut.

And then there is Endeavour. Those early capsules were small – it was said that you didn’t get into Mercury, you put it on. But the shuttle is, by comparison, enormous, and you can’t help being impressed when you see it up close. I spent ages wandering around it, examining the scorch marks on the heat-resistant tiles and the engines, and marvelling at the sheer bulk of the spacecraft.

I thought about the astronauts who had flown on her 25 missions, the courage needed to embark on such journeys – particularly in view of the shuttle disasters – and the sights they would have seen through her windows.

There are fabulous videos of Endeavour being eased through the streets of LA on her way to the museum, the wings barely squeezing past trees and lampposts (see below).

The shuttle is displayed horizontally in a hangar-like pavilion, but there are plans to show her standing vertically in a new building, the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center. She would be attached to the other shuttle components, an external fuel tank and two solid-rocket boosters. This would provide a unique chance to see an entire 60 metres high shuttle vehicle in launch position.

I checked with the museum to see how the plan was progressing, and was told that it’s hoped construction will begin soon. It will then take three years to complete the project.

In the Sixties, as the US closed in on the Moon with successive flights and then triumphantly reached its surface, human space exploration felt like the future.

But today, as we look back 50 years to that first Moon landing and spacecraft have become museum exhibits, it seems to belong to the past. Tomorrow’s World has become yesterday’s world.

Mankind lost the capacity to send astronauts to the Moon after the final Apollo mission in 1972 following mission cutbacks. It seemed a strange decision at the time, and even more so looking back now. All the expense, the effort, the expertise, the resources devoted to putting people on the Moon; the lives of three astronauts killed when Apollo 1 caught fire.

Then, a little more than three years after the first landing, the Apollo programme was wound up, the ability to reach another celestial body surrendered. The US has not been able to launch people into space since the last shuttle flight in 2011.

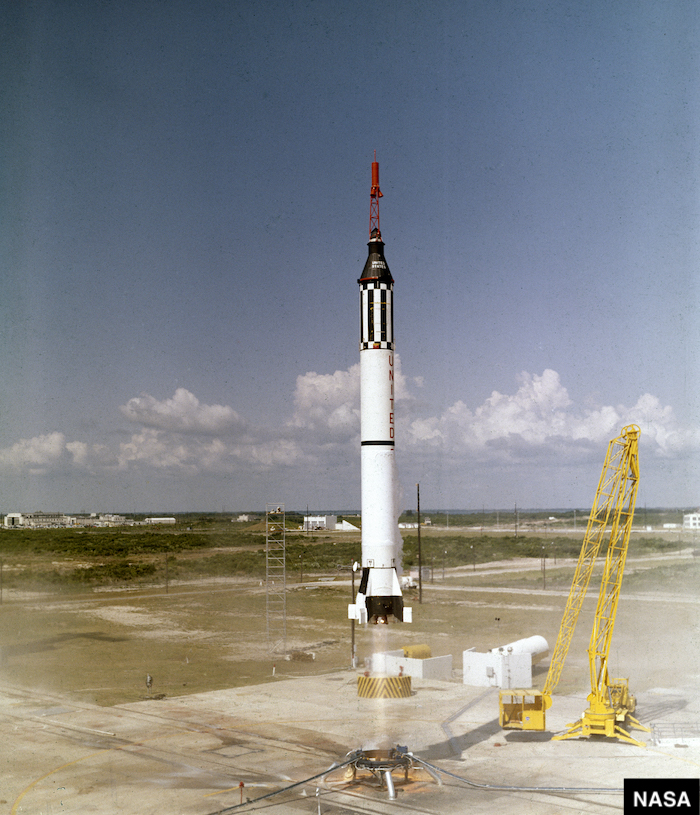

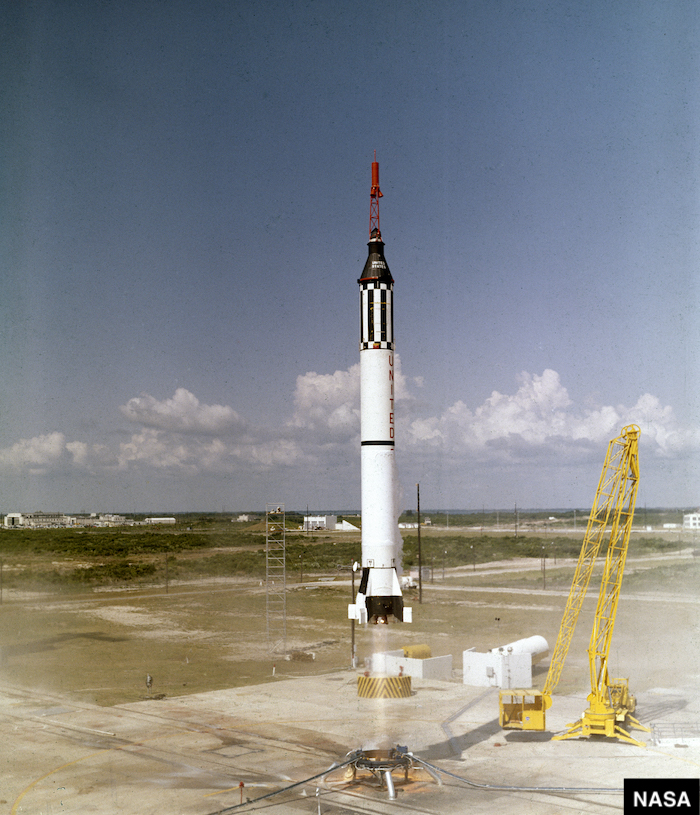

The mission completed by the California Science Center’s Apollo capsule involved climbing 230 kilometres to low-Earth orbit, rather than flying 384,000 km to the Moon, so it did not need the mighty Saturn V to propel it. Instead, it was launched on a far smaller and skinnier Saturn IB, and in order to fit the launchpad the vehicle had to be propped up on a stand. This seems as good a metaphor as any for the reduced horizons and ambition of America’s space programme.

Decades of chatter about human missions to Mars have come to nothing. Is there any reason to think all the current talk about returning to the Moon and going on to Mars will bear fruit?

NASA’s Artemis programme is intended to land a man and the first woman on the Moon in 2024. However, space expert Miriam Kramer, writing for Axios on July 2, said the giant rocket the programme will use, the Space Launch System, is “years behind schedule”. She added that it was not clear whether Congress would allocate the money needed to return to the Moon by 2024.

And she quoted John Logsdon of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute as saying: “The program we have executed to return to exploration is in no way comparable to Apollo in intensity or commitment.”

The growth of the commercial launch sector, the prospect of suborbital tourist joyrides and the rest are all very well. But they hardly compare to the exploits of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, and the other Apollo crews.

It’s strange to think that I, and others my age, have in our lifetime witnessed the transformation of science fiction into reality, and then into history.

Top tip: Endeavour is a popular attraction so timed reservations are needed every day – check out the museum’s website (link below) for details.

Updated January 2020

Return to Tranquility Base

THIS remarkable photo shows the Apollo 11 landing site, known as Tranquility Base, viewed in 2009 from NASA’s unmanned Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The object tagged LM is the descent stage of the Eagle lunar module, left behind when the crew blasted back into space in the ascent stage. The dark tracks were made by the footsteps of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

They lead to a TV camera and two scientific instruments indicated by the initials LRRR and PSEP that were placed on the surface by the astronauts. The discarded cover was from one of the instruments. The LRRR – Laser Ranging Retroflector – was designed to provide information about the distance between the Moon and the Earth, and according to NASA it’s still providing data to this day.

The track to the right of the LM was formed when, towards the end of the Moon walk, Armstrong decided to have a look at a crater called Little West. While there, he took the second photo looking back at the lunar module, with his shadow in the foreground.

MORE INFO

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

LET'S KEEP IN TOUCH!

Endeavour

Encounter

How the Space Age Ended Up as a Museum Exhibit

COLIN SIMPSON

Space shuttle Endeavour, California Science Center, Los Angeles, US

IWAS about to step aboard one of Captain Nemo’s submarines at Walt Disney World in Florida, when suddenly everyone around me started shouting and pointing.

Gazing up, I saw what they were looking at – the second space shuttle mission was blasting off from the John F. Kennedy Space Center 60 miles away.

The shuttle Columbia was a small white speck rising steadily on a column of smoke. For someone who had been entranced by space travel since childhood, this was quite a moment.

When I was at school Freedom 7, the Mercury capsule Alan Shepard flew in when he became America’s first astronaut in 1961, was displayed at a museum in my hometown. If this was intended to create an interest in space among young people, then it certainly worked with me.

I visited the museum in Edinburgh often to peer at the spacecraft, which was clad in protective clear plastic. I listened as John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, gave a speech there.

And I never missed an episode of a BBC TV science show called Tomorrow’s World which covered the run-up to the first Moon landing in lavish detail.

That shuttle launch happened in November 1981, and I saw it as I was nearing the end of an East Coast tour from New York to Florida. I also visited the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington to see the space exhibits and touch the little piece of moon rock on display.

A few days after witnessing the launch from afar I went to the space centre. I travelled on a bus along the road on which the shuttle had been transported to Launchpad 39A where the takeoff had happened.

The same roadway had carried the giant Apollo 11 Saturn V Moon rocket to the pad. While at the complex, I gawped in wonder at the sheer size of a Saturn V that lay in sections along the side of a road.

The Dish, a film about a communications team in Australia that helped to relay TV pictures of the Apollo 11 moon landing, was released in 2000. A colleague in his twenties who liked the movie said he wished he’d been alive during that pioneering era of space travel to witness it all first-hand. I was surprised by this remark, as if he had been he would no longer be young with most of his life ahead of him. But I guess it was a reflection of the fascination space travel holds for so many.

Certainly, my interest in the subject continues to this day, and on a more recent visit to the States I was delighted to get to see a space shuttle, Endeavour, at much closer range.

It’s on permanent display at the California Space Center in Los Angeles. It’s obvious as soon as you arrive that this is no ordinary museum.

Standing next to the car park is a unique trainer version of the A-12 Blackbird, a supersonic high-altitude spy plane developed and built by Lockheed for the CIA as a successor to the U-2. The A-12 was produced as a “black op”, flew for only a few years in the 1960s and its existence remained secret until the mid-1990s.

The museum has other historic aviation exhibits and there are sections devoted to ecosystems, innovation and the life sciences. But for me the standout attractions were the spacecraft from each stage of the US’s spaceflight programme.

There’s the Mercury capsule that carried a chimpanzee called Ham into space in preparation for Shepard’s flight. There’s the two-man Gemini 11 capsule used by astronauts Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad in 1966.

And there’s the three-man Apollo command module that linked up with an orbiting Russian Soyuz spacecraft in 1975 in the first international human space flight mission. This module had been built to fly to the Moon in a planned Apollo 18 mission that was cancelled after funding for the programme was cut.

And then there is Endeavour. Those early capsules were small – it was said that you didn’t get into Mercury, you put it on. But the shuttle is, by comparison, enormous, and you can’t help being impressed when you see it up close. I spent ages wandering around it, examining the scorch marks on the heat-resistant tiles and the engines, and marvelling at the sheer bulk of the spacecraft.

I thought about the astronauts who had flown on her 25 missions, the courage needed to embark on such journeys – particularly in view of the shuttle disasters – and the sights they would have seen through her windows.

There are fabulous videos of Endeavour being eased through the streets of LA on her way to the museum, the wings barely squeezing past trees and lampposts (see below).

The shuttle is displayed horizontally in a hangar-like pavilion, but there are plans to show her standing vertically in a new building, the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center. She would be attached to the other shuttle components, an external fuel tank and two solid-rocket boosters. This would provide a unique chance to see an entire 60 metres high shuttle vehicle in launch position.

I checked with the museum to see how the plan was progressing, and was told that it’s hoped construction will begin soon. It will then take three years to complete the project.

In the Sixties, as the US closed in on the Moon with successive flights and then triumphantly reached its surface, human space exploration felt like the future.

But today, as we look back 50 years to that first Moon landing and spacecraft have become museum exhibits, it seems to belong to the past. Tomorrow’s World has become yesterday’s world.

Mankind lost the capacity to send astronauts to the Moon after the final Apollo mission in 1972 following mission cutbacks. It seemed a strange decision at the time, and even more so looking back now. All the expense, the effort, the expertise, the resources devoted to putting people on the Moon; the lives of three astronauts killed when Apollo 1 caught fire.

Then, a little more than three years after the first landing, the Apollo programme was wound up, the ability to reach another celestial body surrendered. The US has not been able to launch people into space since the last shuttle flight in 2011.

The mission completed by the California Science Center’s Apollo capsule involved climbing 230 kilometres to low-Earth orbit, rather than flying 384,000 km to the Moon, so it did not need the mighty Saturn V to propel it. Instead, it was launched on a far smaller and skinnier Saturn IB, and in order to fit the launchpad the vehicle had to be propped up on a stand. This seems as good a metaphor as any for the reduced horizons and ambition of America’s space programme.

Decades of chatter about human missions to Mars have come to nothing. Is there any reason to think all the current talk about returning to the Moon and going on to Mars will bear fruit?

NASA’s Artemis programme is intended to land a man and the first woman on the Moon in 2024. However, space expert Miriam Kramer, writing for Axios on July 2, said the giant rocket the programme will use, the Space Launch System, is “years behind schedule”. She added that it was not clear whether Congress would allocate the money needed to return to the Moon by 2024.

And she quoted John Logsdon of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute as saying: “The program we have executed to return to exploration is in no way comparable to Apollo in intensity or commitment.”

The growth of the commercial launch sector, the prospect of suborbital tourist joyrides and the rest are all very well. But they hardly compare to the exploits of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, and the other Apollo crews.

It’s strange to think that I, and others my age, have in our lifetime witnessed the transformation of science fiction into reality, and then into history.

Top tip: Endeavour is a popular attraction so timed reservations are needed every day – check out the museum’s website (link below) for details.

Updated January 2020

Return to Tranquility Base

THIS remarkable photo shows the Apollo 11 landing site, known as Tranquility Base, viewed in 2009 from NASA’s unmanned Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The object tagged LM is the descent stage of the Eagle lunar module, left behind when the crew blasted back into space in the ascent stage. The dark tracks were made by the footsteps of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

They lead to a TV camera and two scientific instruments indicated by the initials LRRR and PSEP that were placed on the surface by the astronauts. The discarded cover was from one of the instruments. The LRRR – Laser Ranging Retroflector – was designed to provide information about the distance between the Moon and the Earth, and according to NASA it’s still providing data to this day.

The track to the right of the LM was formed when, towards the end of the Moon walk, Armstrong decided to have a look at a crater called Little West. While there, he took the second photo looking back at the lunar module, with his shadow in the foreground.

MORE INFO

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE CENTER site: Informative source for details about visiting the museum, exhibits and special exhibitions. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE