COLIN SIMPSON

Remembering the Early Days of Diving

FOR many divers of a certain age, it all started with the James Bond film Thunderball. Until then, the only time you saw divers on screen was in documentaries such as Jacques Cousteau’s The Silent World and Hans Haas’s adventures with sharks.

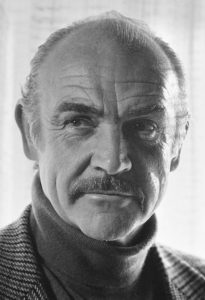

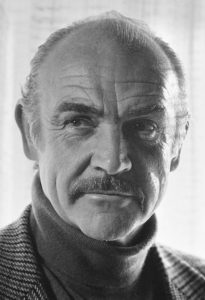

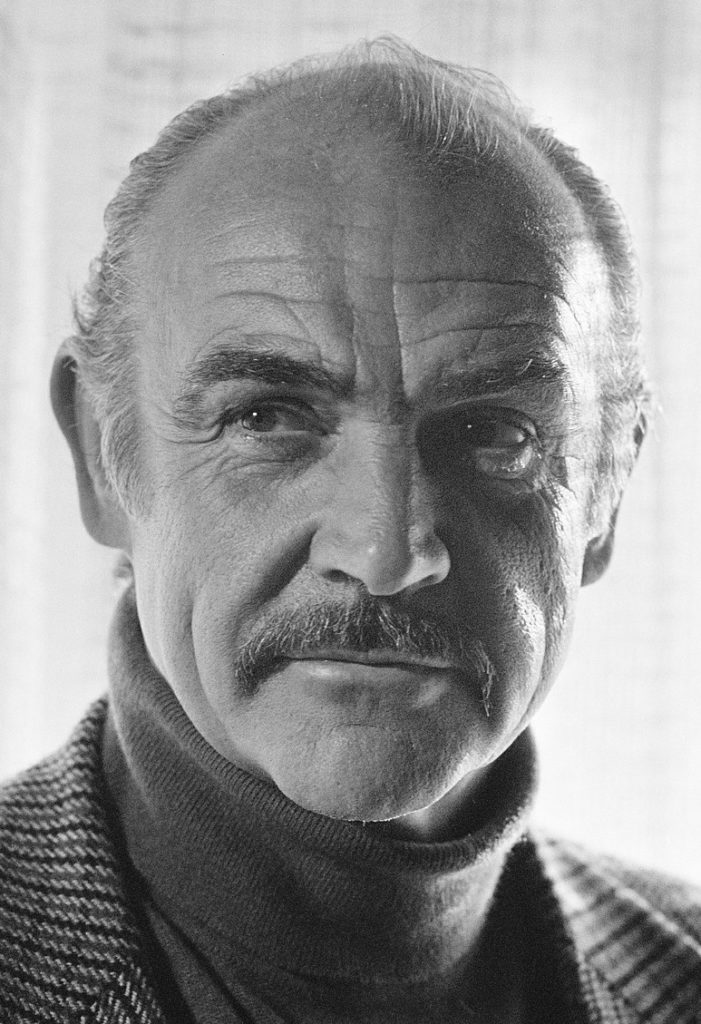

These pioneering works are classics, but for a schoolboy growing up in Edinburgh, Scotland – hometown of the greatest Bond, Sean Connery – there was something missing.

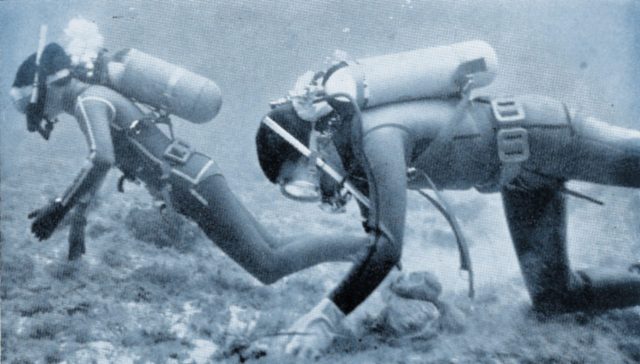

But all that changed with the release of Thunderball. The film features extensive scenes involving divers including a spectacular speargun battle between the sub-aquatic forces of good and evil. The aqualungs that enabled the divers to breathe underwater seemed amazing enough then, but in addition there were fabulous gadgets such as one-man tow sleds with built-in spearguns, and some of the divers parachuted into the water. I watched it all wide-eyed.

The Bond magic transformed the image of diving, turning it from a naval specialisation or the subject of Sunday afternoon TV documentaries into something thrilling, exotic and glamorous. PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, which in turn led the transformation of the sport into a global commercial leisure-industry giant – was founded in 1966, the year after Thunderball‘s release. As for me, I decided I would become a diver, and as soon as I was old enough I joined the sub-aqua club at my school, George Heriot’s in Edinburgh.

But diving back then was not only rather different from the way it was portrayed in Thunderball – compared with today it was incredibly primitive. One essential in those early days that is rarely seen in kitbags now was… talcum powder.

Most wetsuits were made of bare, unlined neoprene and had to be sprinkled liberally inside with talc before you could put them on, otherwise you couldn’t pull the neoprene over your arms and legs. Divers who’ve grown up with nylon-lined suits that slip easily on and off don’t know they’re alive. Another change I notice when I gaze around an equipment shop now is that everything is in Technicolor. I took up diving during the sport’s Model T Ford era – you could have any colour you liked as long as it was black. Wetsuits, masks, fins – almost all of them were uniformly black.

Improved materials and manufacturing processes mean you can now buy yellow fins, blue fins, red fins – any colour you like, really. And the same goes for wetsuits, masks and snorkels.

Huge strides have been made in the area of instrumentation. My first depth gauge was a simple and inaccurate affair consisting of a little transparent plastic tube attached around a plastic disc that you strapped to your wrist. The tube was open at one end and as you went deeper water pressed in further against the column of air trapped inside. You checked how deep you were by noting where the water and air met in relation to a scale printed on the disc. Now it seems amazing that we entrusted our safety to such a device.

Nowadays, of course, there are incredibly sophisticated diving computers that tell how deep you are, how long you can remain safely underwater and a host of other information. Even Q from the Bond films would be impressed.

Between us the members of my club had only one submersible pressure gauge, a battered device of questionable accuracy. But nowadays you can of course get wireless ones! You wear them on your wrist and an electronic transmitter connected to the tank sends a signal indicating the remaining pressure so you never run out of air.

Today purpose-built dive boats with plenty of shade and racks where air tanks can be stored safely are the norm. My old club’s boat was not nearly as classy. It was a homemade affair – we simply borrowed a boat from someone, turned it upside down and used it as a mould, covering the hull with sheets of fibreglass and slapping on resin. Once the resin had hardened we separated the boat from the fibreglass, added some box sections to give it a semblance of strength and – voila! – we had our own boat.

Such a craft probably broke every marine safety regulation even then, but we were happy enough using it, hauling it onto the roof of our second-hand minibus and securing it with ropes before heading off to a dive site. It was never the most sturdy of crafts – the brittle fibreglass cracked easily and frequently had to be patched up.

In the exciting climax of Thunderball, the Disco Volante, the yacht belonging to villain Emilio Largo, famously splits in two – the front half is revealed to be a large, powerful speedboat in which Largo attempts to escape. I always felt our boat could very easily have split in two as well, though not by design.

The club’s land transport was not much better. We had a succession of ancient, worn-out vans and minibuses in which we travelled all over Scotland and beyond. Once we went from Edinburgh to Cornwall and Land’s End – a round trip of 1,200 miles – in a small, battered furniture van. A dozen of us sat on the floor in the back surrounded by wetsuits, air tanks and catering-size tins of baked beans and rice pudding.

Something that has not changed over the years is the distrust felt by fishermen towards divers. On that trip we drove into the Cornish port of Penzance but quickly left to the sound of our own footsteps as the locals made it very clear they did not want us in their waters. They were afraid we would interfere with their lobster pots, but like most divers we would never have thought of doing so – apart from anything else, you could easily lose a finger to those large claws.

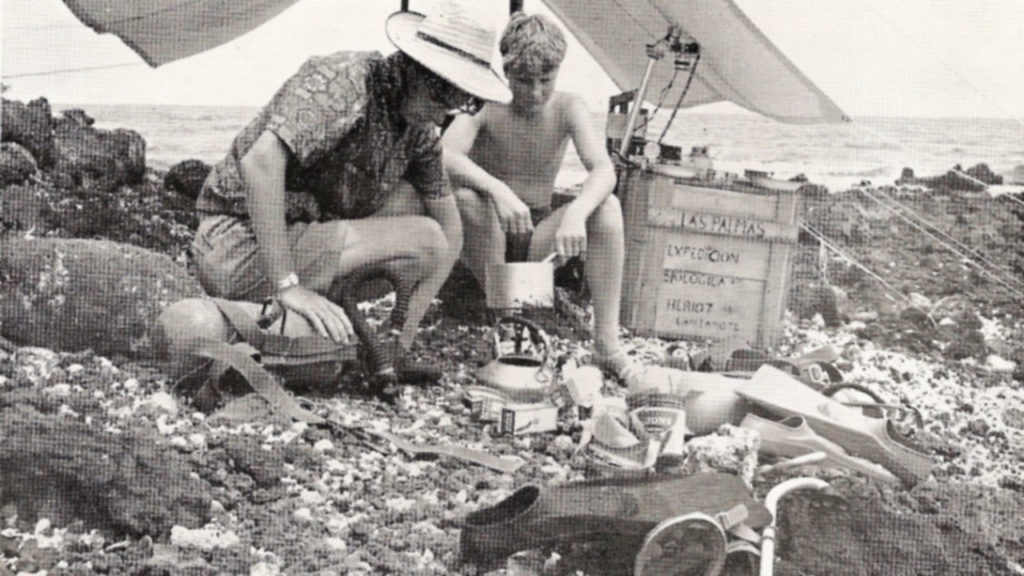

One year the club went on a diving trip overseas, to Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. Closer to home, we visited dive sites near picturesque Scottish towns and villages such as St Abbs, Dunbar, Oban and Ullapool. For deep diving we went to Loch Long, whose steep sides made it ideal.

Since then, to indulge in a little dive boat bragging, I’ve explored underwater in many countries including the Maldives, the Seychelles, Mauritius, Oman, Vietnam, the United Arab Emirates and on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. I enjoyed trips from Dubai, not because of the quality of the diving which is not great, but because I went with the dive school of a five-star hotel, and the level of luxury was a million miles away from home-made boats and talcum powder.

One thing I particularly remember about those early days diving in Scotland was the sheer numbing cold. We went into the water throughout the year, even in midwinter, and I’ve never forgotten the initial shock when the chill water gushed into my wetsuit.

I actually went into the water one time when ice was forming at the edge of the rocks where they jutted into the sea – sounds impossible, but I swear it’s true. Nowadays advances in equipment have solved this problem, as many divers in the UK use drysuits to keep out the cold.

The buoyancy control device, now an essential in every diver’s kitbag, was virtually unheard of in the Seventies. One or two models were available but I never saw anyone using one.

The alternative air source – a second regulator in case the first one broke – is again a standard piece of equipment today, but had not even been developed back then. And the use by sports divers of nitrox – now readily available at many dive centres – likewise lay well in the future.

Then there are Kevlar gloves, LED torches, sophisticated underwater cameras… the list of innovations goes on and on. Though the basic principle of the most essential piece of equipment of all, the regulator, remains basically unchanged, in almost every other area of diving equipment design there have been the most amazing advances.

Now, if only someone could invent an air tank that becomes weightless as you clamber back onto the boat at the end of a dive…

Top photo and black-and-white sub-aqua club images supplied by George Heriot’s School; Sean Connery picture by Skeeze/Pixabay.

April 2019

MORE INFO

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

RELATED

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 VIRTUAL ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 VIRTUAL ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

LET'S KEEP IN TOUCH!

James Bond, Home-Made

Boats, and Talc

COLIN SIMPSON

Remembering the Early Days of Diving

FOR many divers of a certain age, it all started with the James Bond film Thunderball. Until then, the only time you saw divers on screen was in documentaries such as Jacques Cousteau’s The Silent World and Hans Haas’s adventures with sharks.

These pioneering works are classics, but for a schoolboy growing up in Edinburgh, Scotland – hometown of the greatest Bond, Sean Connery – there was something missing.

But all that changed with the release of Thunderball. The film features extensive scenes involving divers including a spectacular speargun battle between the sub-aquatic forces of good and evil. The aqualungs that enabled the divers to breathe underwater seemed amazing enough then, but in addition there were fabulous gadgets such as one-man tow sleds with built-in spearguns, and some of the divers parachuted into the water. I watched it all wide-eyed.

The Bond magic transformed the image of diving, turning it from a naval specialisation or the subject of Sunday afternoon TV documentaries into something thrilling, exotic and glamorous. PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, which in turn led the transformation of the sport into a global commercial leisure-industry giant – was founded in 1966, the year after Thunderball‘s release. As for me, I decided I would become a diver, and as soon as I was old enough I joined the sub-aqua club at my school, George Heriot’s in Edinburgh.

But diving back then was not only rather different from the way it was portrayed in Thunderball– compared with today it was incredibly primitive. One essential in those early days that is rarely seen in kitbags now was… talcum powder.

Most wetsuits were made of bare, unlined neoprene and had to be sprinkled liberally inside with talc before you could put them on, otherwise you couldn’t pull the neoprene over your arms and legs. Divers who’ve grown up with nylon-lined suits that slip easily on and off don’t know they’re alive. Another change I notice when I gaze around an equipment shop now is that everything is in Technicolor. I took up diving during the sport’s Model T Ford era – you could have any colour you liked as long as it was black. Wetsuits, masks, fins – almost all of them were uniformly black.

Improved materials and manufacturing processes mean you can now buy yellow fins, blue fins, red fins – any colour you like, really. And the same goes for wetsuits, masks and snorkels.

Huge strides have been made in the area of instrumentation. My first depth gauge was a simple and inaccurate affair consisting of a little transparent plastic tube attached around a plastic disc that you strapped to your wrist. The tube was open at one end and as you went deeper water pressed in further against the column of air trapped inside. You checked how deep you were by noting where the water and air met in relation to a scale printed on the disc. Now it seems amazing that we entrusted our safety to such a device.

Nowadays, of course, there are incredibly sophisticated diving computers that tell how deep you are, how long you can remain safely underwater and a host of other information. Even Q from the Bond films would be impressed.

Between us the members of my club had only one submersible pressure gauge, a battered device of questionable accuracy. But nowadays you can of course get wireless ones! You wear them on your wrist and an electronic transmitter connected to the tank sends a signal indicating the remaining pressure so you never run out of air.

Today purpose-built dive boats with plenty of shade and racks where air tanks can be stored safely are the norm. My old club’s boat was not nearly as classy. It was a homemade affair – we simply borrowed a boat from someone, turned it upside down and used it as a mould, covering the hull with sheets of fibreglass and slapping on resin. Once the resin had hardened we separated the boat from the fibreglass, added some box sections to give it a semblance of strength and – voila! – we had our own boat.

Such a craft probably broke every marine safety regulation even then, but we were happy enough using it, hauling it onto the roof of our second-hand minibus and securing it with ropes before heading off to a dive site. It was never the most sturdy of crafts – the brittle fibreglass cracked easily and frequently had to be patched up.

In the exciting climax of Thunderball, the Disco Volante, the yacht belonging to villain Emilio Largo, famously splits in two – the front half is revealed to be a large, powerful speedboat in which Largo attempts to escape. I always felt our boat could very easily have split in two as well, though not by design.

The club’s land transport was not much better. We had a succession of ancient, worn-out vans and minibuses in which we travelled all over Scotland and beyond. Once we went from Edinburgh to Cornwall and Land’s End – a round trip of 1,200 miles – in a small, battered furniture van. A dozen of us sat on the floor in the back surrounded by wetsuits, air tanks and catering-size tins of baked beans and rice pudding.

Something that has not changed over the years is the distrust felt by fishermen towards divers. On that trip we drove into the Cornish port of Penzance but quickly left to the sound of our own footsteps as the locals made it very clear they did not want us in their waters. They were afraid we would interfere with their lobster pots, but like most divers we would never have thought of doing so – apart from anything else, you could easily lose a finger to those large claws.

One year the club went on a diving trip overseas, to Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. Closer to home, we visited dive sites near picturesque Scottish towns and villages such as St Abbs, Dunbar, Oban and Ullapool. For deep diving we went to Loch Long, whose steep sides made it ideal.

Since then, to indulge in a little dive boat bragging, I’ve explored underwater in many countries including the Maldives, the Seychelles, Mauritius, Oman, Vietnam, the United Arab Emirates and on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. I enjoyed trips from Dubai, not because of the quality of the diving which is not great, but because I went with the dive school of a five-star hotel, and the level of luxury was a million miles away from home-made boats and talcum powder.

One thing I particularly remember about those early days diving in Scotland was the sheer numbing cold. We went into the water throughout the year, even in midwinter, and I’ve never forgotten the initial shock when the chill water gushed into my wetsuit.

I actually went into the water one time when ice was forming at the edge of the rocks where they jutted into the sea – sounds impossible, but I swear it’s true. Nowadays advances in equipment have solved this problem, as many divers in the UK use drysuits to keep out the cold.

The buoyancy control device, now an essential in every diver’s kitbag, was virtually unheard of in the Seventies. One or two models were available but I never saw anyone using one.

The alternative air source – a second regulator in case the first one broke – is again a standard piece of equipment today, but had not even been developed back then. And the use by sports divers of nitrox – now readily available at many dive centres – likewise lay well in the future.

Then there are Kevlar gloves, LED torches, sophisticated underwater cameras… the list of innovations goes on and on. Though the basic principle of the most essential piece of equipment of all, the regulator, remains basically unchanged, in almost every other area of diving equipment design there have been the most amazing advances.

Now, if only someone could invent an air tank that becomes weightless as you clamber back onto the boat at the end of a dive…

Top photo and black-and-white sub-aqua club images supplied by George Heriot’s School; Sean Connery picture by Skeeze/Pixabay.

April 2019

MORE INFO

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

RELATED

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 VIRTUAL ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 VIRTUAL ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

LET'S KEEP IN TOUCH!

James Bond, Home-Made Boats, and Talc

Remembering the Early Days of Diving

COLIN SIMPSON

FOR many divers of a certain age, it all started with the James Bond film Thunderball. Until then, the only time you saw divers on screen was in documentaries such as Jacques Cousteau’s The Silent World and Hans Haas’s adventures with sharks.

These pioneering works are classics, but for a schoolboy growing up in Edinburgh, Scotland – hometown of the greatest Bond, Sean Connery – there was something missing.

But all that changed with the release of Thunderball. The film features extensive scenes involving divers including a spectacular speargun battle between the sub-aquatic forces of good and evil.

The aqualungs that enabled the divers to breathe underwater seemed amazing enough then, but in addition there were fabulous gadgets such as one-man tow sleds with built-in spearguns, and some of the divers parachuted into the water. I watched it all wide-eyed.

The Bond magic transformed the image of diving, turning it from a naval specialisation or the subject of Sunday afternoon TV documentaries into something thrilling, exotic and glamorous. PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, which in turn led the transformation of the sport into a global commercial leisure-industry giant – was founded in 1966, the year after Thunderball‘s release.

As for me, I decided I would become a diver, and as soon as I was old enough I joined the sub-aqua club at my school, George Heriot’s in Edinburgh.

But diving back then was not only rather different from the way it was portrayed in Thunderball – compared with today it was incredibly primitive. One essential in those early days that is rarely seen in kitbags now was… talcum powder.

Most wetsuits were made of bare, unlined neoprene and had to be sprinkled liberally inside with talc before you could put them on, otherwise you couldn’t pull the neoprene over your arms and legs. Divers who’ve grown up with nylon-lined suits that slip easily on and off don’t know they’re alive.

Another change I notice when I gaze around an equipment shop now is that everything is in Technicolor. I took up diving during the sport’s Model T Ford era – you could have any colour you liked as long as it was black. Wetsuits, masks, fins – almost all of them were uniformly black.

Improved materials and manufacturing processes mean you can now buy yellow fins, blue fins, red fins – any colour you like, really. And the same goes for wetsuits, masks and snorkels.

Huge strides have been made in the area of instrumentation. My first depth gauge was a simple and inaccurate affair consisting of a little transparent plastic tube attached around a plastic disc that you strapped to your wrist.

The tube was open at one end and as you went deeper water pressed in further against the column of air trapped inside. You checked how deep you were by noting where the water and air met in relation to a scale printed on the disc. Now it seems amazing that we entrusted our safety to such a device.

Nowadays, of course, there are incredibly sophisticated diving computers that tell how deep you are, how long you can remain safely underwater and a host of other information. Even Q from the Bond films would be impressed.

Between us the members of my club had only one submersible pressure gauge, a battered device of questionable accuracy. But nowadays you can of course get wireless ones! You wear them on your wrist and an electronic transmitter connected to the tank sends a signal indicating the remaining pressure so you never run out of air.

Today purpose-built dive boats with plenty of shade and racks where air tanks can be stored safely are the norm. My old club’s boat was not nearly as classy.

It was a homemade affair – we simply borrowed a boat from someone, turned it upside down and used it as a mould, covering the hull with sheets of fibreglass and slapping on resin. Once the resin had hardened we separated the boat from the fibreglass, added some box sections to give it a semblance of strength and – voila! – we had our own boat.

Such a craft probably broke every marine safety regulation even then, but we were happy enough using it, hauling it onto the roof of our second-hand minibus and securing it with ropes before heading off to a dive site. It was never the most sturdy of crafts – the brittle fibreglass cracked easily and frequently had to be patched up.

In the exciting climax of Thunderball, the Disco Volante, the yacht belonging to villain Emilio Largo, famously splits in two – the front half is revealed to be a large, powerful speedboat in which Largo attempts to escape. I always felt our boat could very easily have split in two as well, though not by design.

The club’s land transport was not much better. We had a succession of ancient, worn-out vans and minibuses in which we travelled all over Scotland and beyond. Once we went from Edinburgh to Cornwall and Land’s End – a round trip of 1,200 miles – in a small, battered furniture van. A dozen of us sat on the floor in the back surrounded by wetsuits, air tanks and catering-size tins of baked beans and rice pudding.

Something that has not changed over the years is the distrust felt by fishermen towards divers. On that trip we drove into the Cornish port of Penzance but quickly left to the sound of our own footsteps as the locals made it very clear they did not want us in their waters. They were afraid we would interfere with their lobster pots, but like most divers we would never have thought of doing so – apart from anything else, you could easily lose a finger to those large claws.

One year the club went on a diving trip overseas, to Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. Closer to home, we visited dive sites near picturesque Scottish towns and villages such as St Abbs, Dunbar, Oban and Ullapool. For deep diving we went to Loch Long, whose steep sides made it ideal.

Since then, to indulge in a little dive boat bragging, I’ve explored underwater in many countries including the Maldives, the Seychelles, Mauritius, Oman, Vietnam, the United Arab Emirates and on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

I enjoyed trips from Dubai, not because of the quality of the diving which is not great, but because I went with the dive school of a five-star hotel, and the level of luxury was a million miles away from home-made boats and talcum powder.

One thing I particularly remember about those early days diving in Scotland was the sheer numbing cold. We went into the water throughout the year, even in midwinter, and I’ve never forgotten the initial shock when the chill water gushed into my wetsuit.

I actually went into the water one time when ice was forming at the edge of the rocks where they jutted into the sea – sounds impossible, but I swear it’s true. Nowadays advances in equipment have solved this problem, as many divers in the UK use drysuits to keep out the cold.

The buoyancy control device, now an essential in every diver’s kitbag, was virtually unheard of in the Seventies. One or two models were available but I never saw anyone using one.

The alternative air source – a second regulator in case the first one broke – is again a standard piece of equipment today, but had not even been developed back then. And the use by sports divers of nitrox – now readily available at many dive centres – likewise lay well in the future.

Then there are Kevlar gloves, LED torches, sophisticated underwater cameras… the list of innovations goes on and on. Though the basic principle of the most essential piece of equipment of all, the regulator, remains basically unchanged, in almost every other area of diving equipment design there have been the most amazing advances.

Now, if only someone could invent an air tank that becomes weightless as you clamber back onto the boat at the end of a dive…

Top photo and black-and-white sub-aqua club images supplied by George Heriot’s School; Sean Connery picture by Skeeze/Pixabay.

April 2019

MORE INFO

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FIND OUT about the numerous training courses offered by PADI – the Professional Association of Diving Instructors – at its official site. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

FOR A LESS commercial approach, check out the site of the British Sub-Aqua Club, which has training and resort centres in many countries. READ MORE

RELATED

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

CHOOSING A WINTER holiday destination in Asia can be surprisingly tricky, but we found the perfect place – Phu Quoc in Vietnam. READ MORE

RECOMMENDED

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

WELCOME TO OUR WORLD! Afaranwide’s home page – this is where you can find out about our latest posts and other highlights. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

TOP 10 ATTRACTIONS: Many of the world’s most popular tourists sites are closed because of the coronavirus crisis, but you can still visit them virtually while you’re self-isolating. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

SHIMLA, QUEEN OF THE HILLS: Government officials once retreated to Shimla in the foothills of the Himalayas to escape India’s blazing hot summers. Now tourists make the same journey. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TEN THINGS WE LEARNED: Our up-to-the-minute guide to creating a website, one step at a time. The costs, the mistakes – it’s what we wish we’d known when we started blogging. READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE

TROUBLED TIMES FOR EXPATS: Moving abroad can seem an idyllic prospect, but what happens when sudden upheavals or the inescapable realities of life intrude? READ MORE